For a BBC interview with Professor Biddle on the same subject, click here.

For a later interview with Cat Jarman on the Viking burials in Repton and at Heath Wood, click here.

Viking Repton, by Barry M. Marsden

From 'The Vikings in Derbyshire'

Derbyshire Life & Countryside, March & April 2007

[Two minor additions to the original are shown like this.]

When Professor Martin Biddle and his wife went to Repton in South Derbyshire in 1974 their purpose was to study the architecture of the Anglo-Saxon Church of St Wystan. They little anticipated a 20-year stay that would elucidate the full story of the Viking incursions into the Trent Valley in 873-4 AD. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had recorded that the enemy force, which had first landed in East Anglia in 865 and had rapidly destroyed the latter kingdom, plus Northumbria and Mercia, had taken winter quarters at Repton, but no-one knew its location, and it was uncertain whether any archaeological evidence of the camp had survived. Nineteenth century discoveries, however, including a Scandinavian-type hogsback tombstone and part of a Viking sword, uncovered in the vicinity of the church, suggested that this area was the focus of the camp, a view reinforced by the finding of a Viking-style axe in the churchyard in 1923, and another Viking sword in a Repton attic. These were further hints that the encampment must have been in the general area surrounding St Wystan's.

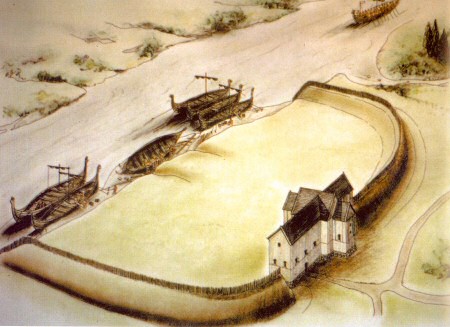

In 1976 Biddle located a U-shaped ditch and bank on the south bank of the River Trent, enclosing some 3.6 acres and incorporating the Anglian church in a central position along the defence line, serving both as an entrance and command centre. Both ends of the earthwork impinged on the Trent north of the church where a 20ft high bluff rose above the river, where longships could have moored to bring supplies and reinforcements to the invaders as necessary.

Other evidence for the Viking presence was found around the east end of the church, which had been founded as a monastic site in the 7th century AD. The early church was provided with a mausoleum in the form of the famous crypt which still survives under the chancel in the present structure. This subterranean room became a burial vault for several Mercian kings of the 8th-9th century, including Aethelbald (d.757), Wiglaf (d.840), and Wigstan (Wystan), the last murdered in a power-struggle in 849. The burials were placed, after defleshment, in niches in the crypt walls. Wigstan later became a saint and the crypt a place of pilgrimage.

In 1976 Biddle located a U-shaped ditch and bank on the south bank of the River Trent, enclosing some 3.6 acres and incorporating the Anglian church in a central position along the defence line, serving both as an entrance and command centre. Both ends of the earthwork impinged on the Trent north of the church where a 20ft high bluff rose above the river, where longships could have moored to bring supplies and reinforcements to the invaders as necessary.

Other evidence for the Viking presence was found around the east end of the church, which had been founded as a monastic site in the 7th century AD. The early church was provided with a mausoleum in the form of the famous crypt which still survives under the chancel in the present structure. This subterranean room became a burial vault for several Mercian kings of the 8th-9th century, including Aethelbald (d.757), Wiglaf (d.840), and Wigstan (Wystan), the last murdered in a power-struggle in 849. The burials were placed, after defleshment, in niches in the crypt walls. Wigstan later became a saint and the crypt a place of pilgrimage.

The Biddles found a group of important Viking interments in the present churchyard, immediately north and south of the crypt. The most significant was the skeleton of a 35-45 year-old man, nearly 6 ft tall, lying in a grave north of the church which was originally marked by a 12 in square wooden post which may once have been carved and painted. In an abutting grave was a second male inhumation, aged around 20, perhaps a retainer to his older companion. The elder male was a person of obvious importance, who seems to have died in a battle or skirmish, perhaps with the Anglian locals around the time of the Trent Valley incursion. The warrior had fallen from a blow to the skull, and whilst on the ground had been despatched with a sword-cut that had severed the femoral artery. He was buried in true pagan fashion; round his neck was a thong holding two glass beads, a small silver Thor's hammer and a leaded bronze fastener. A leather belt around his waist had been secured with a decorated copper-alloy buckle, and by his left side was an iron sword in a fleece-lined wooden scabbard covered with leather, with another copper-alloy buckle holding a suspension-strap for the sheath. By the sword hilt was a folding iron knife, plus a second knife with a wooden handle, whilst halfway down the scabbard was an iron key. Between the thighs was the tusk of a wild boar and lower down, perhaps originally in a bag or box, was the humerus of a jackdaw.

A leather belt around his waist had been secured with a decorated copper-alloy buckle, and by his left side was an iron sword in a fleece-lined wooden scabbard covered with leather, with another copper-alloy buckle holding a suspension-strap for the sheath. By the sword hilt was a folding iron knife, plus a second knife with a wooden handle, whilst halfway down the scabbard was an iron key. Between the thighs was the tusk of a wild boar and lower down, perhaps originally in a bag or box, was the humerus of a jackdaw.

The skeleton in the adjoining grave may also have died violently from a cut to the right side of his head. He had an iron knife at his waist and may well have been a squire or weapon-bearer killed at the same time as his lord and united with him in death. Both burials had been subsequently covered with an oblong setting of broken sandstones heaped up over the double-grave. Other intact Scandinavian-type burials in the vicinity included one with a gold finger-ring, and was neatly dated by five silver pennies minted in the mid-870s. South of the chancel were three other contemporary graves, though none contained weapons.

Other evidence for the Viking presence in the area comes from the once-enigmatic group of 59 generally small burial mounds situated in Heath Wood, Ingleby, on a ridge 350 ft above the Vale of Trent some 2ľ miles south-east of Repton. They were first located by the Derbyshire barrow-digger Thomas Bateman, who dug a few of them in 1855 and presciently dated them to the early Viking era. The barrows were further probed in the 1940s and 50s, and latterly between 1998-2000. All the tumuli covered cremations, many apparently in situ, together with gravegoods which included fragmentary items of dress and weaponry. Many of the dead seem to have been burned on sections of boat planking, a rite which might well be a token form of ship-burial.

The Viking barrow cemetery is a site unique in Britain. It seems to have been used between 873-7 and was possibly the principal interment area of members of the Great Viking Army. The dead may have included battle casualties, plus those who died of disease or other causes. A detachment of this host might well have remained behind their fortifications at Repton until the partition of Mercia between the Scandinavians and their Anglian puppet Ceolwulf in 877. The Heath Wood barrow group should now take its rightful place as one of the most important sites of early Viking Age England.

Before their much delayed departure from Repton, the Biddles had one more surprise in store, the finding of a unique Viking mass-burial, first discovered by a labourer in 1686 and destined to be as dramatic as anything they had so far uncovered.

The burial site in the vicarage garden, seen from the west. For a sense of scale, note the kneeling figure in the centre. In the foreground steps lead into the western room, whilst the far ranging rod marks the site of the mass-grave. The two circular holes in the foreground were ritual pits, and traces of the surrounding kerb can be identified. The long slots on the right mark the graves of later burials.

As part of their operations in the village they investigated 250 year-old reports of a mass burial discovered around 1686 by a labourer named Thomas Walker who was seeking stone in a close west of the church. The original account seemed so fantastical as to be beyond belief, but it stated that Walker found a two-roomed subterranean structure some 15 ft square, originally roofed by 'decayed wooden joyces'. Inside, the astonished rustic found a stone coffin, containing 'a Skeleton of a Humane Body Nine Foot long.' Around this singular interment were 'One Hundred Humane Skeletons, with their Feet pointing to the Stone Coffin.' Walker removed the skull of the main burial, but this was soon lost. He also revealed that the floor of the sunken building was stone-paved, and in the outer wall was the frame of a doorway, with steps leading down into the western room.

Some 100 years later the landowner George Guilbert reinvestigated the site, but merely reported finding 'a vault' in which 'were found vast quantities of human bones, as if collected ... and thrown in a heap together.' Finally, in 1914, the supercilious cleric and antiquary Charles Cox dug a narrow trench across the area and later wrote that 'ignorance and folly had entirely destroyed what remains there may have been'. The Biddles' later excavation showed how perfunctory Cox's opening must have been.

Between 1980-86 the Biddles thoroughly investigated the remains of this unique location, finding the disordered bones of at least 264 individuals whose defleshed bones had originally been stacked, charnel-wise, against the walls of the inner or easterly room of the building, which was probably constructed as a mausoleum to hold the body of the Mercian monarch Merewahl who died in 757AD. It was in a ruinous state in 873 when the Vikings cut it down to ground level and floored the eastern room with a thick layer of marl. The central burial and the mass bone deposit was laid directly on this layer as a single deliberate act.

Between 1980-86 the Biddles thoroughly investigated the remains of this unique location, finding the disordered bones of at least 264 individuals whose defleshed bones had originally been stacked, charnel-wise, against the walls of the inner or easterly room of the building, which was probably constructed as a mausoleum to hold the body of the Mercian monarch Merewahl who died in 757AD. It was in a ruinous state in 873 when the Vikings cut it down to ground level and floored the eastern room with a thick layer of marl. The central burial and the mass bone deposit was laid directly on this layer as a single deliberate act.

When Walker stumbled upon this amazing collective burial he had rummaged among the bone stack, dismantled the primary burial and subsequently taken away much of the stonework of the walls. Biddle's careful reinvestigation found many items missed by the earlier delvers, including a fine iron axe, a sword blade, two large seaxes, a key, chisel, and five silver pennies, all minted between 872-4, and securely dating the deposit to the Viking occupation of Repton between 873-4.

The south-west pit containing the skeletons of the four young males sacrificed as part of the rituals associated with the closure of the barrow. The stone setting at centre left may have supported a wooden marker. Just to the right of the feet of the nearest skeleton are the jaws of a sheep.

The south-west pit containing the skeletons of the four young males sacrificed as part of the rituals associated with the closure of the barrow. The stone setting at centre left may have supported a wooden marker. Just to the right of the feet of the nearest skeleton are the jaws of a sheep.

The central 'coffin' might well have been a slab-built cist, with the collective bones neatly stacked around it, completely filling up the wall space around the coffin. Heavy timber joists had then been laid on the tops of the cut-down walls to form a roof subsequently covered with flat slabs. The sunken structure had then been sealed by a low stone cairn, itself masked by a mound of pebbles which was edged by a kerb of upright stones. Careful clearing of the area around the rectangular barrow revealed four sunken pits which may have served for organic offerings; they were later filled with stones. Finally, at the southwest corner of the heap was a large pit containing four juvenile skeletons, one accompanied by a sheep's jaw. [Bone analysis shows that only one of these may have been local.] A square hole lined with upright stones on the south side of the hollow may have held a timber grave marker. The carefully-arranged interments must represent human sacrifices associated with the closing of the tumulus.

Of the bones piled in the eastern chamber, 82 per cent were male, and of the 69 skulls rescued, only one was over 45 years old. The male bones were all robust in appearance, and suggest a Scandinavian population such as the Viking host which wintered in the Repton area at the time suggested by the coin evidence found within the barrow.

It is obvious that the burial mound must have housed some outstanding Viking figure, who died during that winter and was interred with blatant pagan rites and accompanied by fellow-warriors whose excarnated bones seem to have been disinterred to accompany the great man in death. They were probably soldiers who had died during the campaign, subsequently exhumed and piled in the chamber to lie with the body of their leader.

Who was the exceptional individual worthy of such an outstanding communal burial effort? The Biddles believe him to be Ivar the Boneless, possibly the brother of Healfdeane, one of the leaders of the Viking force at Repton in 873-4. Ivar was noted as a man of exceptional cruelty and ferocity, and his nickname may indicate that he lacked legs, or may simply mean that he was long-legged or tall. The Viking force split into two in 874 and the occasion may have prompted the high status, elaborate and complex burial in the cairn placed on the bluff above the Trent at Repton. The entombment is without parallel in Europe during the Viking age, and it is interesting that one saga notes that Ivar died and was buried in England 'in the manner of former times', an allusion to the fact he was interred in a barrow.

The main facts relating to this unique sepulchre are beyond dispute. It can be precisely dated to the time of Ivar's death, and the tumulus was raised by the army of which he had been a leader at the exact moment it was about to break up forever. The singular monument lies on a crest above [and designed to be seen from] the River Trent, not only a great natural divide, but the historic boundary between north and south. Its placement within a former Mercian mausoleum, with a mass of contemporary human remains, is also significant, and it does seem that a convincing claim can be established as to the identity of the man in the mound.