Christianity in Repton

| Prehistory |

|

||||||

| The Repton bluff has long been the setting for human activity. The first traces appear in the fourth or fifth millennium BC. There is then a long gap in the evidence, but archaeological excavations in 2013 indicate that the site was continuously occupied from about the 4th or 5th centuries BC, with evidence of both Roman and Anglo-Saxon settlement. | |||||||

| Repton, Capital of Mercia | |||||||

|

|||||||

From the 7th to the 9th centuries, Repton (Hrewpandum) was a principal residence of the royal family of Mercia, at its greatest a very considerable region which stretched from the Ribble to the Thames, from the Humber to the (Bristol) Avon, from the fens of East Anglia to the Welsh marches. Timber buildings discovered north and south of the church may represent the halls and other structures of the estate centre. There were at least three stages of major timber structures before the first church was built, suggesting that the earliest may date back to around 600.

The Birth of Christianity

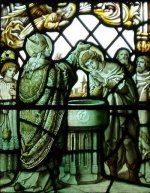

Repton's recorded history begins in 653 AD when Peada, son of the great King Penda of Mercia married Elfleda, daughter of Oswy, King of Northumbria, which had converted to Christianity some 20 years previously. A condition of the royal marriage was that Peada should be baptised and receive Christian teaching. To this end, Elfleda brought with her four priests, monks from Lindisfarne, including Diuma who c. 656 became the first bishop of Mercia and introduced Christianity to the kingdom. The other three were Adda, Betti, and Cedd. In 669, Chad, the brother of Cedd and the fourth bishop of Mercia, moved the see to Lichfield.

|

The transfer of the see to Lichfield How much this was influenced by the development of Christianity nationally is impossible to say. However, the Council of Whitby, which united the Roman and Celtic churches and brought the great monasteries under the control of abbots obedient to Rome, took place in 664. Further, in 668 Theodore of Tarsus was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury; arriving in 669, he toured the English dioceses, redistricting, founding new ones, and creating more bishops. |

In about 660, the royal family founded Repton Abbey close to the new church. This was a double monastery - for men and women - ruled by an abbess who was of noble, perhaps royal, rank. The first recorded abbess was Werberga. It was here that Guthlac received his tonsure from Abbess Aelfthryth in about 697 AD.

|

Monasteries and the aristocracy

At this period, monks and nuns were drawn almost exclusively from the aristocracy. It is estimated that between the 7th and early 8th centuries, some 30 kings and queens, including Sigeberht and Aethelred of Mercia, entered monasteries, together with countless others of noble birth, warriors and court retainers. Despite the hard regime, in a troubled world the prime concern of everyone was to save his soul from hell. However, Bede criticised the low standards of some monasteries, alleging that they were in effect aristocratic households masquerading as monateries to avoid paying taxes. |

Merewahl, king of the Magonsætan, said to be a son of Penda perhaps by an earlier marriage and thus a half-brother of Wulfhere, was probably buried at Repton in the latter part of the seventh century.

Repton crypt was constructed in the first half of the 8th century, during the reign of King Aethelbald (reigned 716 - 757). It may have been built originally as a baptistery, sunk 1.2 m into the ground over a spring and drained to the east by a deep stone-built channel constructed no later than 740. It was later converted into a mausoleum, perhaps to receive the body of King Aethelbald himself. Together with the church which rises above it, this crypt today forms one of the principal monuments of Anglo-Saxon architecture. It consisted simply of four walls with a roof possibly of wood. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 757 King Aethelbald of Mercia was buried at Repton following his murder at Seckington, twelve miles away.

King Wiglaf (reigned 827 - 840) transformed both the crypt and the east end of the church. In the crypt, four 'barley-sugar' columns and high-quality vaulting now carried the enormous weight of the Anglo-Saxon chancel which Wiglaf built above. Wiglaf's burial at Repton was recorded by Florence of Worcester. He also relates that, following his murder, St Wystan was buried "in the famous monastery of Repton in the mausoleum of his grandfather Wiglaf". Miracles took place at Wystan's tomb and the church became a place of pilgrimage. So many came to visit his shrine that the royal mausoleum needed two staircases, north and south, to manage the flow. Before the end of the ninth century, Wystan had come to be regarded as a saint. By this time a central space and north and south porticos had been added to the church. The buildings had multi-coloured window glass and exceptional stone sculpture in standing crosses and grave covers. Stucco with architectural mouldings was used on the walls of the western building. Lead was used, perhaps for roofing. Silver-gilt, silver, and copper-alloy pins and brooches were dropped and coins lost. Vividly coloured glass beakers were plentiful, and wheel-turned pottery of the most up-to-date kind.

The Vikings

However, in the autumn of 873, after more than two centuries of high status as a royal and religious centre, the life of this community was shattered with the arrival of the Danish Great Army. Led by four 'kings', the four marauding Viking armies took over not only the buildings, rich in people and possessions, but also Mercian royal authority. Mercia as an independent kingdom came to an end; the royal family fled. The remains of St Wystan were taken away by escaping monks; they were returned to Repton when the Viking menace disappeared, but later, King Cnut of England (reigned 1016-1035) had them removed to Evesham Abbey.

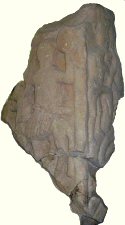

The Vikings, perhaps 2,000 in all, destroyed the abbey and fortified an encampment by the Trent, using the church as its central strongpoint, to serve as a winter fortress for the winter of 873 - 874. Many Vikings and Anglo-Saxons died at this time; under the present Vicarage lawn lie the foundations of an 8th century stone chapel; on top of it was a Viking burial mound containing the remains of 200 Viking men and 49 Anglo-Saxon women. Among the vast number of ancient burials around the east end of St Wystan's was that of a Viking warrior, with his sword by his side. Close to the crypt also was found the "Repton Stone", part of an Anglo-Saxon cross-shaft showing on one side a kilted warrior on a horse. This is thought to be a representation of King Aethelbald of Mercia, who died in 757 and was entombed in the crypt. (The right-hand face represents the mouth of Hell. A monster with a human head and a serpent's body devours two human figures. They are dressed in knee-length breeches with cross-gartered legs.)

The Vikings, perhaps 2,000 in all, destroyed the abbey and fortified an encampment by the Trent, using the church as its central strongpoint, to serve as a winter fortress for the winter of 873 - 874. Many Vikings and Anglo-Saxons died at this time; under the present Vicarage lawn lie the foundations of an 8th century stone chapel; on top of it was a Viking burial mound containing the remains of 200 Viking men and 49 Anglo-Saxon women. Among the vast number of ancient burials around the east end of St Wystan's was that of a Viking warrior, with his sword by his side. Close to the crypt also was found the "Repton Stone", part of an Anglo-Saxon cross-shaft showing on one side a kilted warrior on a horse. This is thought to be a representation of King Aethelbald of Mercia, who died in 757 and was entombed in the crypt. (The right-hand face represents the mouth of Hell. A monster with a human head and a serpent's body devours two human figures. They are dressed in knee-length breeches with cross-gartered legs.)

The Great Army divided and departed in the autumn of 874, taking with them slaves, horses and food, as well as the treasure of the monastery. When they arrived, Repton had been a prosperous monastery for men and women, with a church, two mausoleums and monastic buildings, enjoying an ancient relationship with the kings of Mercia. When they left, the wooden buildings of the abbey were burnt, the church, which had been used as a gatehouse to a fortified enclosure, was set on fire and so badly damaged that the upper half of its walls had to be completely rebuilt, including the windows and roofs. Earthworks had cut through the cemeteries east and west of the church. The ancient mausoleum to the west had been cut down, its eastern room used as a burial chamber. Stone crosses were wrecked, dressed stone blocks broken into fragments.

Referring to the activities of the Viking bands and armies, Alfred remarked that 'everything was ransacked and burned'.

Although the church was restored in the late ninth and early tenth centuries, Repton never regained its former status. Nothing is ever heard again of the monastery founded at Repton two centuries before. None of its books have survived, and of its archive only one charter is known, its text preserved in the records of the recipient, the archbishop and community of Christ Church, Canterbury. It was a ruthless assertion by the Vikings of their own ancient religion, carried through without regard for people or possessions, and making no distinction between the sacred and the secular.

For a detailed article on the Vikings in Repton, click here.

A Mediaeval Church

For three centuries after the Viking incursion Repton's history is shadowy. The church was restored during the first quarter of the tenth century, some 40 to 50 years later, and from this time acted as a minster serving a large region probably equivalent to Derbyshire south of Trent, the area known in Domesday Book as Walecros wapentake, and by 1156 as Repton wapentake. That St Wystan's continued to be of special importance is demonstrated by Domesday's statement that, unusually, there were two priests serving the church. The church has never since ceased its parochial function, although by the twelfth century ecclesiastical developments had reduced its area to a smaller, but still very extensive parish including the seven chapelries of Bretby, Foremark, Ingleby, Newton Solney, Measham, Smisby, and Ticknall.

In the early twelfth century a small but strongly defended motte and bailey castle was built on the Repton bluff to control the fords across the river, a link in Earl Ranulf of Chester's string of fortresses along the middle and upper Trent. Following Ranulf's death in 1153, his widow Matilda, Countess of Chester, founded an Augustinian Priory on the site of the castle, close beside the east end of the ancient church. The canons came into residence about 1172, ministering for nearly four centuries to many parishes in South Derbyshire. Repton Priory was also a considerable landowner, not always enjoying a harmonious relationship with the local peasantry. This was exemplified in 1364 when an armed mob broke down the gates of the Priory and attacked the Bishop of Lichfield and the Prior.

Probably in the mid-thirteenth century, the Augustinian canons built their own splendid church (of the Holy Trinity and St Mary), but St Wystan's continued to flourish and was much enlarged between the 13th and 15th centuries. The 212 foot high tower and spire date from the 15th century.

The Dissolution

Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries claimed Repton Priory as a victim in 1538. The buildings were sold in 1539 to Thomas Thacker (Steward to Thomas Cromwell, who directed the dissolution) and on his death were inherited by his son, Gilbert Thacker. The latter achieved a certain notoriety as the man responsible for destroying the Priory. In about 1550, alarmed at the prospect, under Mary Tudor, of a religious house being re-established on his property, he assembled an army of workmen and (it is said) had the greater part of the Priory, including its magnificent church, demolished in a single day. Gilbert's succinct comment was that it was necessary "to destroy the nest, for fear the birds should build there again". In 1557, the Thacker family sold to the executors of Sir John Port, of Etwall, the Priory guest house, one of the few remaining buildings left standing by Gilbert, together with the site of the demolished claustral buildings. The guest house, known today as the Old Priory, became the original home of Repton School, for whose foundation Sir John's will provided. For the last four centuries Repton School has been only the latest occupant of this long settled site: from the School Yard at Repton, it has been said, one can see "buildings dating from every century back at least to the tenth", or rather, as we now know, to the eighth.